This is the first post in a series on Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick. TBD whether we’ll be going through the novel comprehensively or making a selection of chapters. In any event we begin at the beginning.

We pick up Moby-Dick. It is a fat book. We have heard of it before, no doubt. Perhaps we have already read it, maybe long ago, maybe many times (it is a bewitching kind of book that calls one back to it). We know at the least it is about a white whale, about Captain Ahab, who pursues the white whale monomaniacally (that word is closely bound to the book in the popular consciousness). Perhaps we even know the book’s opening command, "Call me Ishmael.” Whatever knowledge of the plot we carry into our reading will not diminish our enjoyment of the book. For it is an unusual book, strange and delightful and expansive, greater than its plot and larger than its size even suggests.

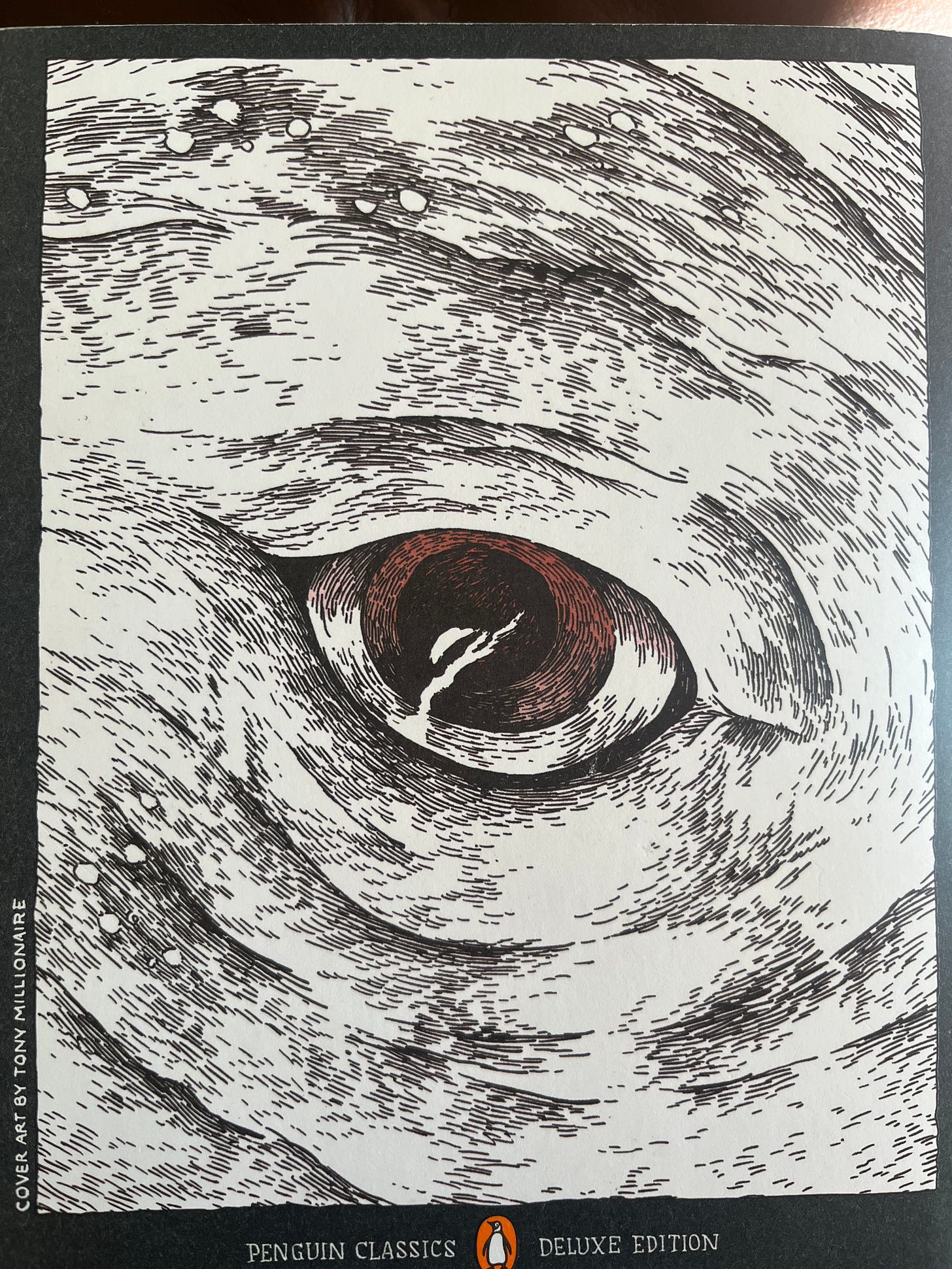

All this foreknowledge is fitting for the first chapter of Moby-Dick, titled “Loomings.” In one sense the title refers to Ishmael’s adumbrations of his impending whaling voyage, as a looming event, about to occur. In another sense it refers to the physical bulk of the whale that will tower over his tale. He tells us of a “great whale… a portentous and mysterious monster” (6.1), “one hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air” (6.2).1 In yet another meaning, perhaps the most important, the title suggests the loom on which the Fates weave the destinies of mankind. More on this in a moment.

First, a brief summary of the chapter. Moby-Dick is a long and sprawling book, but its chapters are often brief. Still, some struggle with the language (I’ve heard it called archaic) and it can be helpful to lay down an agreed-upon sequence of events before diving into analysis. In this first chapter, we are introduced to Ishmael and he explains how he came to be on a whaling ship. This includes Ishmael’s theory on the appeal of the sea, both historical (Persia, Greece) and contemporary (Manhattan), and his reasoning for taking to the sea as a sailor rather than a passenger.

Now we can do some close reading. Below I reproduce the full first paragraph. The beginnings and endings of books are always important. This is a particularly beautiful (and famous) one.

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago—never mind how long precisely—having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen, and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball. With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship. There is nothing surprising in this. If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean with me.

This passage is packed to the gills. See how much we learn about Ishmael. He is an eccentric—one of the great literary eccentrics!—prone to melancholy yet full of humor. Who but an eccentric would propose a voyage at sea as an alternative to suicide (“substitute for pistol and ball;” “Cato throws himself upon his sword; I take quietly to the ship.”) This is not just an unusual idea, but a romantic one, emblematic of Ishmael’s character. How many of us wish we could do the same sometimes, pick up and leave our problems behind and embark on an adventure?

We are also introduced to Ishmael as a classicist,2 a motif that threads his way through the novel. He makes reference to Cato, Greece, and Persia. Ishmael is a kind of historian, certainly a man of the Enlightenment. He seeks an understanding of the world with great effort and records his findings with flourish. Yet he is a new issue in that his intellect is fixed upon America,3 specifically on Nantucket and the whale trade. Rather humorously, Ishmael fixes his story’s place in the historical record, or as he puts it “the grand programme of Providence” (7.2):

Grand Contested Election for the Presidency of the United States

WHALING VOYAGE BY ONE ISHMAEL

BLOODY BATTLE IN AFGHANISTAN

This brings us to another analogy introduced in this first chapter, that of history as a drama. The fates are “stage managers” who have put Ishmael down for a “shabby part of a whaling voyage, when others were set down for magnificent parts in high tragedies” (7.3). We will see as the novel progresses Ishmael treat his voyage as a high drama in its own right, with heroes, villains, and tragic downfalls. At times, he will abandon his post as narrator and the story will be rendered in speeches or lines of dialogue, as in a play.

To what end? you ask. What is the purpose of all this artifice, of this long account of a whaling voyage, this heavy book? Let us look at the last paragraph.

By reason of these things, then, the whaling voyage was welcome; the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open, and in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, midmost of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air. (8.2)

My goodness. Is your ass out of your seat? Here is your answer! Here is Ishmael the visionary, Ishmael the prophet, verily floating. What an image! His soul is the ark and in file the whales, and there we file in behind them.

A note on citations: I will refer to the 2009 Penguin Books version of the text (the one with the foreword by Nathaniel Philbrick) throughout. I will follow a page and paragraph scheme in most cases (the citations in the sentence above refer to page 6, the first and second paragraphs.

To be precise, the first evidence of Ishmael’s interest in furnishing a historical account is the presence of the two preface sections: “Etymology” and “Extracts,” which I will treat separately. Though they come before the first chapter, they should be read later if one is to make sense out of them.

Ishmael has something in common with Walt Whitman in this respect. Often the narrator’s meditations on America sounds like Whitman’s poems: expansive, transcendentalist, celebratory. Indeed, there is also a common strain with the writing of Thoreau. One may be tempted to argue that this is all just the intellectual soup of the time so to speak, that it makes its way into the book through a kind of osmosis. I would argue that these are kindred souls with common worldviews and artistic interests.