A poor devil's account of the course of literature

Or what I wish I knew when I started reading seriously

It’s in good fashion today to bemoan the scarcity of readers. I suspect people have been making some version of this complaint as far back as you care to go, with varying degrees of validity. One can imagine a Sumerian curmudgeon lamenting the young scribes who refuses to bury their heads in the clay tablets. And he probably had a better case than we do.

In truth, there is no shortage of self-proclaimed lovers of books. Look no further than the wide avenues of Substack, where a small army of enthusiastic amatuers and professionals publishes its cherished thoughts on books. Look at Goodreads; look at BookTok. And look at the sales of the today’s megastars, the Colleen Hoovers and James Pattersons. People are reading. Lots of people!

But, you say, it doesn’t quite feel right. These readers aren’t reading serious literature. It’s fantasy, romance, thriller fiction, or it’s self-help books, all of them hastily or poorly written. You might be on to something. I don’t necessarily subscribe to this vision. Read whatever you want. If that makes you happy, great. Often I think of what Kurt Vonnegut proposed was the goal of art:

I say in speeches that a plausible mission of artists is to make people appreciate being alive at least a little bit. I am then asked if I know of any artists who pulled that off. I reply, ‘The Beatles did’.

So if that Colleen Hoover book makes you appreciate being alive, more power to you. I’m not Harold Bloom. I have no vendetta against Harry Potter or Stephen King. May a thousand flowers bloom — that’s my official position.

But I will say this. If It Ends with Us can do that for you, think of what Mrs. Dalloway can do. Great novels are more fertile grounds for growing.

I don’t think this is an unpopular idea. Most people understand it intuitively. But there is still often a resistance to reading literary fiction. The usual objection is that it’s boring, or hard. And that television and social media have shorted the average attention span so that it cannot deal with a difficult book. David Foster Wallace spoke eloquently1 — better than I can — about these ideas time and time again.

I would add that it isn’t just hard work to read dificult books, but that the average reader is woefully underprepared. Now, I don’t say this as some kind of omniscient scholar; after all, I’ve just recently undertaken the exercise of publicly airing my literary blind spots, a humbling experience. I come from this as someone who wished I had a better picture of the literary landscape when I started to care about books. That’s what this comes down to.

Why is this important? Because among the legion book lovers I’ve seen around here, there are plenty who are interested in reading “the great books.” But I don’t see them going about it the right way.

The first problem is defining “great books,”2 a spiny issue. I mentioned Harold Bloom earlier; he made quite the niche for himself as a definer and promoter of the Western Canon of Literature. Bloom was a lightning rod, thanks in part, no doubt, to his presenting himself as a supercilious and contemptuous, miserable bastard. And the idea of a canon was a politically charged topic even then; it is now a veritable third rail. The only time you’ll hear about the Canon in academia today is when someone is talking about toppling it. Still there are standard-bearers who are willing to launch into battle on the cultural Teutoburg Forests and Cannaes and risk dismemberment and dishonor over establishing a canon and picking the books that should be on it. I am not one of them. But I will say this: any enterprise that nominally sets out to examine “the great books” must at least examine the question what are the great books, either at the outset or along the way. One cannot wade lightly into all the thousands of years of the written word and only fish out a few tomes from the ancient historians and the treatises one liked the most in philosophy class while claiming to be diving into the great literature of the world.

The point of my saying this is not to admonish the benighted ways of these readers. They’re trying. That’s good! My point is to say that we’ve done wrong by them, and it doesn’t have to be this way.

I can recall hazily looking at the books in my childhood home and feeling a great sense of mystery. Not mystery in the sense of intrigue but in the sense of blankness and vague terror; I’ve likened it before to the unexplored areas of the world on ancient maps. For in my childhood home there were a few bookcases and a jumble of books across genres, in no way organized: hardcovers by John Grisham and John le Carré, a fat copy of Gray’s Anatomy on a shelf behind the television, popular history books by Stephen Ambrose, beat-up Raymond Chandler paperbacks and other pulp, ornate old books from garage sales that weren’t really for reading — a motley assortment. And there I was, a bright enough kid with college-educated parents, going to a good public school, and all these books were a big question mark. How could that be?

Here’s how: at that good public high school that I attended, I dutifully read all the assigned books in my English classes. The structure of the classes as I remember them were such that you would read some selection every night and discuss it the next day. There might be a worksheet or a quiz aimed at vocabulary or comprehension (proving you did the reading), and then there were essays periodically. Most were short, modelled on the state exams or AP exams where you have limited time to handwrite your essay. Others were longer and called for the incorporation of sources — these were called “research papers.” The idea of the whole process is to teach some baseline proficiency in reading and writing as skills.

For this reason, the selection of reading material becomes secondary to the practical schooling at hand. But the general goals in choosing books seemed to be exposing students to literary breadth (for instance, we read Homer’s Odyssey and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart sophomore year) and choosing books that would be engaging or relatable to high school students.3 True, the teachers had some discretion and seemed to be interested in making things contemporary when they could; I remember reading A Secret History and The Postman Always Rings Twice as a senior. But it is also true that the teachers were majorly constrained by the allotment of time and the prevailing culture. They got 45 minutes a day. Part of the year had to be dedicated to learning grammar,4 or writing college essays, or reading non-fiction. The classes couldn’t be too hard, or the reading load too heavy, lest a hoard of angry parents descend like locusts. “Little Thaddeus has to get into a Good College. It’s important he gets an A. His future depends on it.” So even if a teacher wished to instill in students a life-long love of the study of literature, he or she faced great challenges.

All that being said, there was undeniably something missing from my instruction. It was clear in the confusion that confronted me when I looked at my family’s bookshelves. It was this confusion that led to a minor personal epiphany.

On the shelves, as I have said, there were names I faintly recognized. One was Kurt Vonnegut, who I mentioned earlier. I remember finding his book Galapagos on the shelf. It must have been high school, a night where nothing was happening. So I sat on the floor and read it, and kept reading it, and my God it was good! I went on to read everything the man wrote when I was a freshman in college, so I can look back and see that it wasn’t nearly his best work. But there was something there, a sense of unity in time and a well-turned plot and his sardonic, absurd wit turned on the long course of humanity. (In the novel, a virus causes infertility across the globe and a great war breaks out, leaving the only healthy survivors a group cruising to the Galapagos Islands, where they shipwreck and repopulate the world. One of the passengers, a survivor of Hiroshima, is pregnant and gives birth to a child with fur like a seal, hastening the evolution of humans into seal-like hybrids. It’s not Slaughterhouse-five, but it’s fun.) It must have been the first time I’d taken down one of these books and realized the immense possibility there on the shelves.

Then, around the same time, I snagged a hardcover of The Sun Also Rises off my father’s nightstand, and Hemingway became my personal hero, as he is to so many young men. What a way to live, I thought. Europe! Bull-fights! Day-drinking! It didn’t get better than that for a 17-year-old kid. But there was also the language itself. Cool and immediate as a breeze, it gave me the feeling of Spain, of Paris. This was magic. And because Hemingway revered the word, I would too.

What I’m getting at here is that I blundered into a love of literature. I was groping along in the dark and happened upon the right book, the right writer. If I didn’t live in a house with books — fiction books — it probably wouldn’t have happened. And I would’ve been the poorer for it. And even then, in the beginning of my journey I was much like the sub-sub-librarian in Moby-Dick who supplies Ishamel his extracts concerning whales.

(Supplied by a Sub-Sub-Librarian)

[It will be seen that this mere painstaking burrower and grub-worm of a poor devil of a Sub-Sub appears to have gone through the long Vaticans and street-stalls of the earth, picking up whatever random allusions to whales he could anyways find in any book whatsoever, sacred or profane. Therefore you must not, in every case at least, take the higgledy-piggledy whale statements, however authentic, in these extracts, for gospel cetology. Far from it. As touching ancient authors generally, as well as the poets here appearing, these extracts are solely valuable or entertaining, as affording a glancing bird’s eye view of what has been promiscuously said, thought, fancied, and sung of Leviathan, by many nations and generations, including your own.

So fare the well, poor devil of a Sub-Sub, whose commentator I am. Thou belongest to that hopeless, sallow tribe which no wine of this world will ever warm; and for whom even Pale Sherry would be too rosy-strong; but with whom one sometimes loves to sit, and feel poor-devilish, too; and grow convivial upon tears; and say to them bluntly, with full eyes and empty glasses, and in not altogether unpleasant sadness — Give it up, Sub-Subs! For by how much the more pains ye take to please the world, by so much the more shall ye for ever go thankless! Would that I could clear out Hampton Court and the Tuileries for ye! But gulp down your tears and hie aloft to the royal-mast with your hearts; for your friends who have gone before are clearing out the seven-storied heavens, and making refugees of long-pampered Gabriel, Michael, and Raphael, against your coming. Here ye strike but splintered hearts together — there, ye shall strike unsplinterable glasses!]

Moby-Dick, “Extracts.”

(A reminder to check out my first post on Moby-Dick if you haven’t already. More to come soon.)

I was a grub-worm in a dark library, and for no good reason. I was given an education in English literature, after all! Yet it was a higgledy-piggledy one.

Luckily, my remedy is simple: a modest — modest — eductation in literary theory and history.5 What I mean by this is just enough to know where you’re at: a rough idea of the various movements and progressions of English literature throughout the years, some of the major figures associated with them, and likewise the schools of thought of literary analysis. I will return here to the image of a “map” of literature. All a young reader (or really a reader of any age) needs filled in is the major roads and the signposts to look out for. Then he can move about he wishes.

My own map took shape when I took a course in Modernist literature. In that course the idea was presented that these writers — Conrad and Joyce and Woolf and T.S. Eliot and so on — were responding to their mileiu and to the books that came before them, the books they read. In this way a generation of writers can produce bodies of work that share certain characteristics. You face the horrors of World War I and the sudden erasure of the rural way of life in favor of the urban; you have been educated in classical literature (I mean Homer and Virgil and the like); you produce something that sounds like The Wasteland or Ulysses: fragmented and highly allusive and dificult to read.

We can apply this line of thinking to other periods and soon the course of literature takes shape. Go back in time from Modernism and you find Victorian literature, where writers are beginning to address some of the same themes. There is the tyranny of the clock with the advent of the railway and standardized time; there is concern for the plight of the poor in cities. But poite society and respectability still dominate. Go forward in time and we get Postmodernism, which is even more fragmented and applies the formal approaches of Modernism in every direction, at times to great extremes.

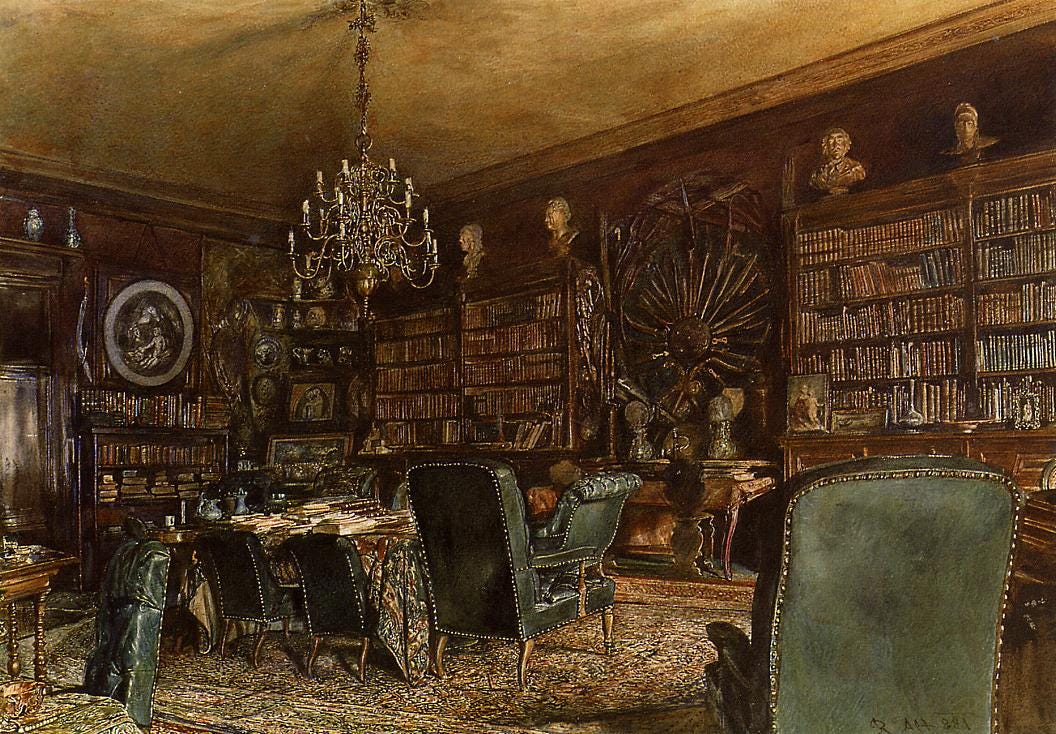

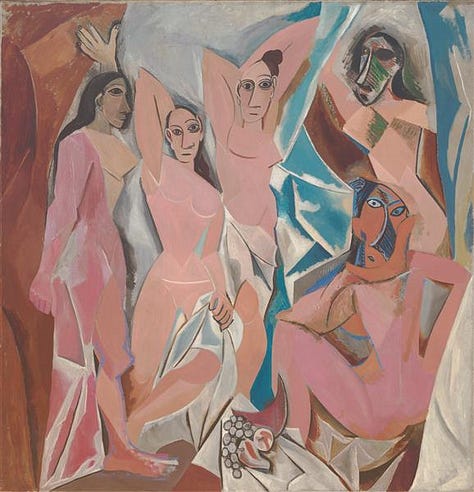

In learning to see this progression in literature, I found it helpful to look at art. For example, the course of Victorian → Modern → Postmodern can be observed in the paintings below. First realism is abondoned and then representation altogether. One can compare, say, Bleak House to Finnegan’s Wake or the “Sirens” chapter of Ulysses.

This was an important revelation for me: that the course of literature through the ages is a continuum. “Books are made out of books,” Cormac McCarthy said in one of his few interviews. “The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” It followed that I could better understand what I read by understanding what its author read. For some time already my map of literature was no longer blank; there were discrete points revealed — Hemingway and Vonnegut, for example. Now I was connecting these points, and the map was rapidly filling.

For the record (not that anyone asked) I prefer Wallace’s nonfiction and commentary to his prose. I think his exhaustively analytical style works better pointed at a problem (lobsters, usage dictionaries, television) than allowed to run in circles for a thousand pages. The juice of Infinite Jest isn’t worth the squeeze.

“Classic literature” is even worse. Next time you’re in your local bookstore take a look at the “classics” section. I’ll bet dollars to donuts that it’s a completely arbitrary selection and at least one book’s inclusion will make you a little bit mad.

The idea of choosing literature that is “relatable” chaps my ass in that one of the major benefits of reading fiction is that it allows you occupy some other’s mind for a while and glean some understanding of humanity from it. All the better if it is an old woman when you’re a young man. Spare the students the old Catcher in the Rye nonsense. Treat them like adults that are capable of absraction and sympathy.

Truly I can only recall spending part of one year, junior year, on grammar. The teacher did a bang-up job. It had never occured to me before than that the placement of commas had discrete rules you can learn. That says something.

I say modest because there is a need for a light touch here. Too much history is a slog and takes time away from the important stuff, the actual reading. And too much theory makes one dogmatic, I think. To the man with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail, and to the Marxist literary critic, every novel looks like a class war. A good reader is sensitive to a text’s own terms and doesn’t impose his own. This is the way to understanding a text. (Of course, if you want to become a theory wonk or literary history makes you deeply happy like nothing else in the world, more power to you.)

![[Moby-Dick] 1. Loomings](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zKlb!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4544e77b-db33-4c52-a9dc-eb05201b6adb_3024x4032.heic)